This time last year, a group of twenty people from around Hull came together to talk about the future of the city.

All over 60 – the eldest born in 1934 – we looked back at the changes over the past 80 years. Central to the discussions was how communities around the city had transformed. Many in the room had lived through the clearance of the neighbourhoods around the Hessle Road, and the creation of Europe’s largest housing estate in Bransholme. In Aarhus too, the 1960’s saw an ambitious re-building of the city at Gellerup following the modernist ideals of Le Corbusier.

The space age of the 1960’s offered a bold future. One lady at the Hull workshop jokingly remembers: “They promised us jet packs…” – but the reality of the 21st century is somewhat different. The dream of flight, for example, is less marked by adventure than it is by queues at the airport, endless security checks and long haul flights full of red-eyed backpackers and business people. Restless sleep and a feeling of being detached and unrooted are the norm. This summer’s British Airways inflight magazine carried a supplement un-ironically called ‘Belonging’ – showing glossy photos of Caribbean islands where those with enough cash to invest in property can buy their way to citizenship.

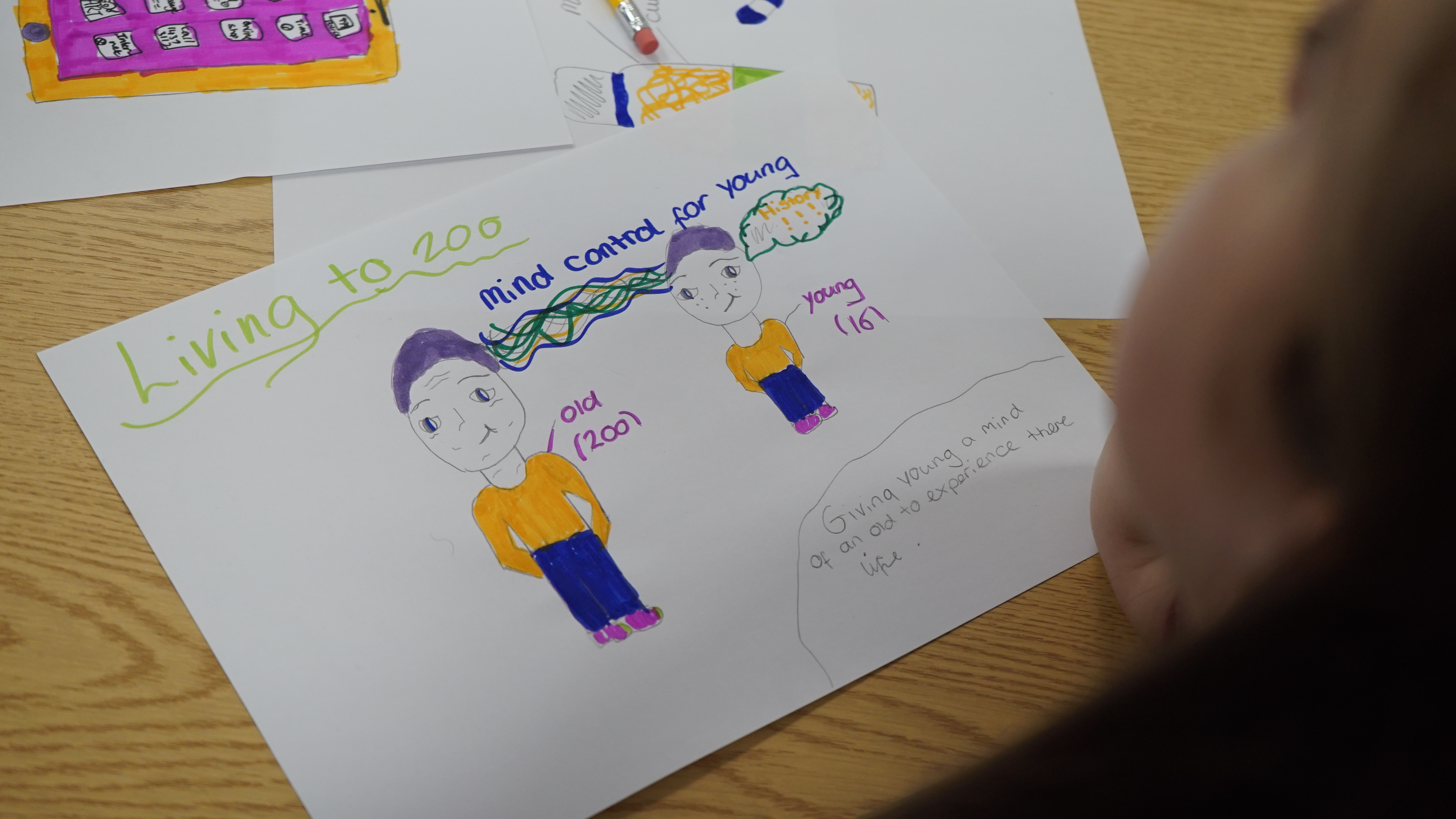

Back in Hull, a feeling of belonging turns out to be central to discussions of the future – though property ownership doesn’t figure at all. Instead, the focus was how to support young people to live in the city, how to support and grow communities, and an unsentimental recognition that the city is bound to change to survive.

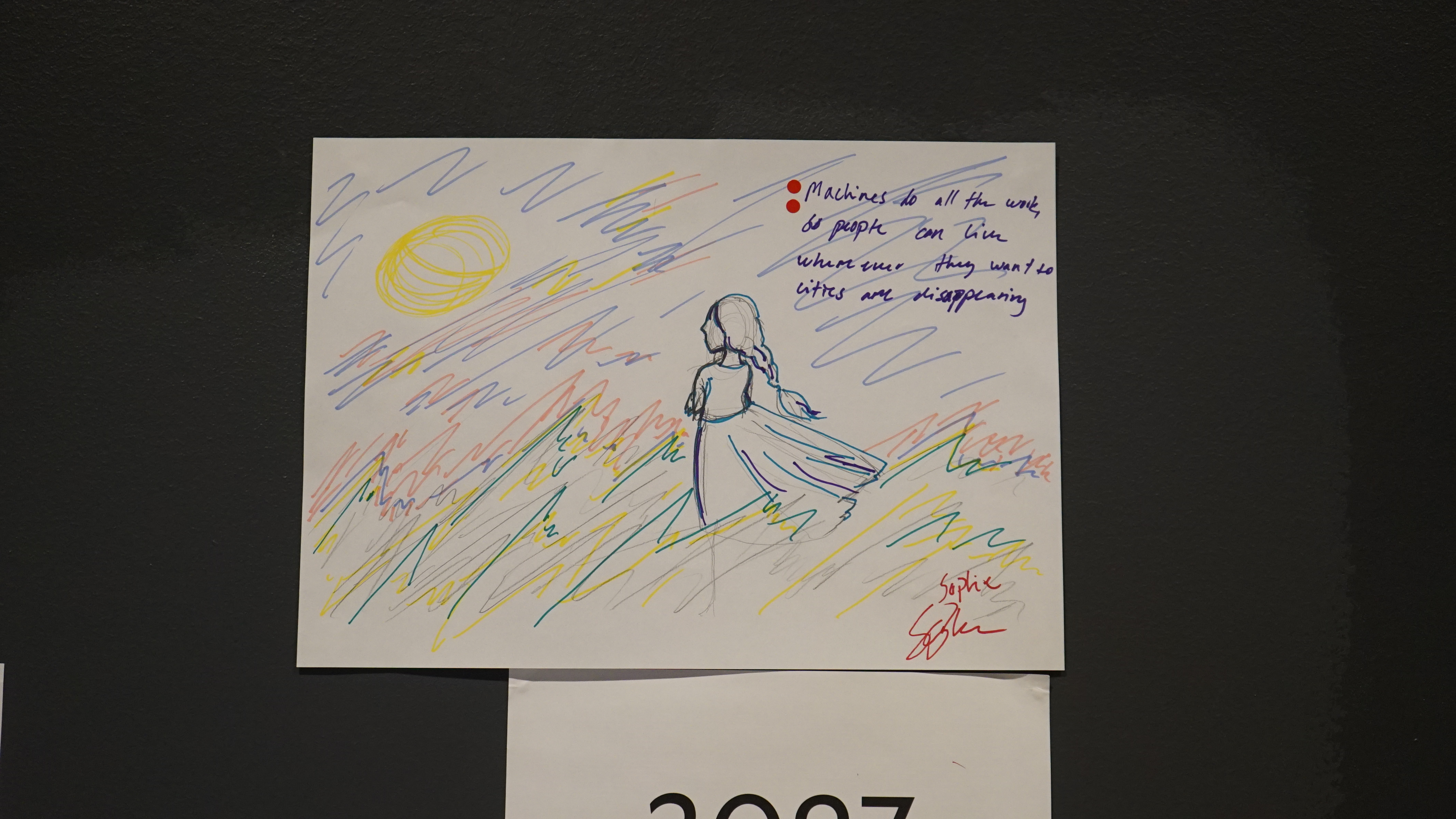

Though there were few firm answers, these discussions and the challenges they raised inspired where we began with the stories for 2097. What is it that makes a community? And what are the things that sustain us in the face of change?